I know I was a very spoilt child and have no recollection of ever being reprimanded for anything. One occasion that sticks in my memory was the day Dr. Dundass was called to the house to look at my very sore throat. I refused to open my mouth and hid under the diningroom table. My mother got a broom and tried to force me out, but I escaped somehow and ran into the garden and climbed the large wattle tree at the back. The African gardener was summoned and told to climb up and fetch me down. When he started up the tree I told him that if he came any higher I would pee in his face, whereupon he beat a hasty retreat and Dr. Dundass went off on his rounds. I don’t remember hearing any more of this and I don’t know if my father was told.

After some time my mother was unable to tolerate quinine and the frequent attacks of malaria finally developed into Blackwater Fever. I remember that she was ill in bed for a long time. Then one day there were several folk in the sittingroom talking about something – my father was holding the enamel jerry pot and I managed to peer over the edge to see what all the fuss was about. I could see that it appeared to be full of blood. In fact this was the colour of her urine (hence the name Blackwater). There was no cure and she was only in hospital for a short time I think, before she died, in 1934. I must have been 6 years old.

She was brought up a Roman Catholic but did not practise her faith and I learnt years later that there was an ugly scene in the hospital when she was dying. One of the Catholic nurses had sent for the priest, Father Hartman, to administer the last rites. My mother did not want to see him and my father had to lock the ward door in order to keep him out and have a few minutes privacy with his dying wife. Father Hartman was told by my father to take himself off since he had not once tried to see my mother or offer help or advice in her life and she had no wish for it now.

Poor Jock learnt of her death from the kindly couple, the Cramms, who ran Kenton College and they were very good to him. I remember a day when everyone wore smart dark suits and there were cars arriving at the house and bouquets of arum lilies being put into a car. A very large lady, known as Aunt Jan, stayed with me until everyone returned and had tea and biscuits. I think this must have been the funeral.

Some time later, my father took me on a picnic in the woods above our house. We had orange juice and a box of chocolate fingers wrapped in gold paper. He explained that Mum had been very ill and had died and that I would go and live with the Newtons. He would call in every day on his way back from the office and on the weekends I could come and stay with him. Ethel and Charles Newton had one son, Michael, who was three. I didn’t cry for my mother – I don’t think small children do react as simply as that – but I must have been distressed about her death because I suffered awful nightmares from time to time at the Newtons.

Michael and I slept in one bedroom and we had mosquito nets suspended from circular wire frames over the beds. I can remember seeing these small red eyes staring at me through the net at the foot of my bed and sometimes they would start to move up the side of the bed getting larger as they neared my head. The only thing I could do to bring my paralysing fear to an end was to jump straight at them, bringing the whole mosquito net down about my ears, ending on the floor in a tangle and waking the entire household. After a while the nightmares ceased. I had a very happy life with Ethel and Charles Newton and he and my father were great friends. I think Jock also spent his holidays there for the first year.

My father realised that Ethel and Charles could not really provide a home for Jock as well as me and felt that he should have an English education at a good school.

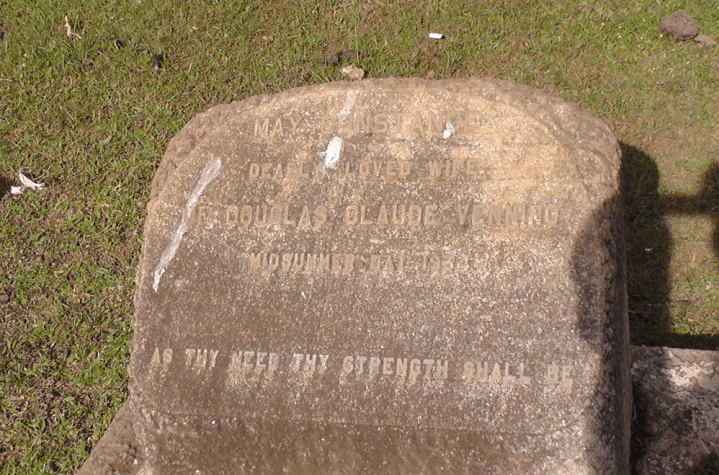

May Constance, dearly loved wife of Douglas Claude Venning, midsummer day 1934, as thy need thy strength shall be